Contents:

Common Names | Parts Usually Used | Plant(s) & Culture | Where Found | Medicinal Properties | Biochemical Information

Legends, Myths and Stories | Uses | Formulas or Dosages | Warning | Resource Links | Bibliography

Scientific Names

- Psilocybe semilanceata

- Psilocybe semilanceata

- Psilocybe hispanica

- Psilocybe mexicana

- Psilocybe cubensis

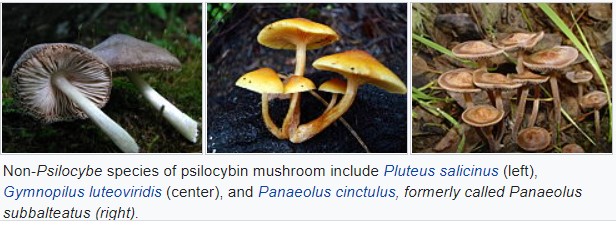

- Pluteus salicinus

- Gymnopilus luteoviridis

- Panaeolus cinctulus

- Panaeolus subbalteatus

Common Names

- Magic mushrooms

- Mushrooms

- Shrooms

- Teonanácatl (Mexican)

Parts Usually Used

Entire mushroom

Back to Top

Description of Plant(s) and Culture

Psilocybin mushrooms, fungi that contain the hallucinogens psilocybin and psilocin

Back to Top

Where Found

Present in varying concentrations in about 200 species of Basidiomycota mushrooms, psilocybin evolved from its ancestor, muscarine, some 10 to 20 million years ago. In a 2000 review on the worldwide distribution of psilocybin mushrooms, these were considered distributed among the following genera: Psilocybe (116 species), Gymnopilus (14), Panaeolus (13), Copelandia (12), Pluteus (6) Inocybe (6), Pholiotina (4) and Galerina (1).

Many of them are found in Mexico (53 species), with the remainder distributed throughout Canada and the US (22), Europe (16), Asia (15), Africa (4), and Australia and associated islands (19). Generally, psilocybin-containing species are dark-spored, gilled mushrooms that grow in meadows and woods in the subtropics and tropics, usually in soils rich in humus and plant debris. Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents, but the majority of species are found in subtropical humid forests.

Back to Top

Medicinal Properties

Due partly to restrictions of the Controlled Substances Act in the United States, research had been frozen until the early 21st century when psilocybin mushrooms were tested for their potential to treat drug dependence, anxiety or mood disorders. In 2018-19, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation for studies of psilocybin in depression disorders.

At low doses, shrooms can change your sense perception, warping surfaces, overlaying visual perception with repetitive geometric shapes, altering colors and changing how sounds are perceived. Hallucinogenic effects include auras around light, “breathing” surfaces and afterimages or “tracers.” Higher doses can cause synesthesia, distort cognizance of time and space, and give the user a sense of melding with the environment. More complex open or closed-eyes visual hallucinations are also possible, but are rarely confused for reality. Using shrooms also produces subjective emotional effects, which can range from hilarity to heightened anxiety. Magic mushrooms also dilate pupils.

Psilocybin in magic mushrooms becomes psilocin in the human body, which binds with serotonin receptors in the brain, particularly receptor 5-HT2C, which regulates the release of neurotransmitter chemicals related to appetite, cognition, anxiety, imagination, learning, memory, mood and perception. Psilocin increases activity in the visual cortex, while decreasing the part of the brain responsible for your ego, or individual sense of self.

Back to Top

Biochemical Information

Present in varying concentrations in about 200 species of Basidiomycota mushrooms, psilocybin evolved from its ancestor, muscarine, some 10 to 20 million years ago.

Present in varying concentrations in about 200 species of Basidiomycota mushrooms, psilocybin evolved from its ancestor, muscarine, some 10 to 20 million years ago.

The effects of psilocybin mushrooms come from psilocybin and psilocin. When psilocybin is ingested, it is broken down by the liver in a process called dephosphorylation. The resulting compound is called psilocin, which is responsible for the psychedelic effects. Psilocybin and psilocin create short-term increases in tolerance of users, thus making it difficult to misuse them because the more often they are taken within a short period of time, the weaker the resultant effects are. Psilocybin mushrooms have not been known to cause physical or psychological dependence (addiction). The psychedelic effects tend to appear around 20 minutes after ingestion and can last up to 6 hours. Physical effects including nausea, vomiting, euphoria, muscle weakness or relaxation, drowsiness, and lack of coordination may occur.

As with many psychedelic substances, the effects of psychedelic mushrooms are subjective and can vary considerably among individual users. The mind-altering effects of psilocybin-containing mushrooms typically last from three to eight hours depending on dosage, preparation method, and personal metabolism. The first 3–4 hours after ingestion are typically referred to as the ‘peak’—in which the user experiences more vivid visuals and distortions in reality. The effects can seem to last much longer to the user because of psilocybin’s ability to alter time perception.

Back to Top

Legends, Myths and Stories

The use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in America was partially stamped out by Catholic missionaries during the Spanish conquest, but continued to be used in indigenous ceremonies in Mexico. In 1957, Life magazine published the account of two ethnomycologists, who participated in just such a ceremony (it was revealed in 2016 that their expedition was funded by the CIA’s Project MKUltra). A year later, Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist who first synthesized LSD, isolated the psychedelic compound psilocybin. Magic mushroom was popularized through the 1960s by researchers and psychedelic gurus, including Timothy Leary, Terence McKenna and Robert Anton Wilson.

Prehistoric rock art near Villar del Humo in Spain, suggests that Psilocybe hispanica was used in religious rituals 6,000 years ago. Mushroom stones and motifs have been found in Guatemala. A statuette dating from ca. 200 CE depicting a mushroom strongly resembling Psilocybe mexicana was found in the west Mexican state of Colima in a shaft and chamber tomb. A Psilocybe species known to the Aztecs as teōnanācatl (literally “divine mushroom”: agglutinative form of teōtl (god, sacred) and nanācatl (mushroom) in Náhuatl) was reportedly served at the coronation of the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II in 1502. Aztecs and Mazatecs referred to psilocybin mushrooms as genius mushrooms, divinatory mushrooms, and wondrous mushrooms, when translated into English. Bernardino de Sahagún reported the ritualistic use of teonanácatl by the Aztecs when he traveled to Central America after the expedition of Hernán Cortés.

After the Spanish conquest, Catholic missionaries campaigned against the cultural tradition of the Aztecs, dismissing the Aztecs as idolaters, and the use of hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms, together with other pre-Christian traditions, was quickly suppressed. The Spanish believed the mushroom allowed the Aztecs and others to communicate with demons. Despite this history the use of teonanácatl has persisted in some remote areas.

The first mention of hallucinogenic mushrooms in European medicinal literature was in the London Medical and Physical Journal in 1799: a man served Psilocybe semilanceata mushrooms he had picked for breakfast in London’s Green Park to his family. The doctor who treated them later described how the youngest child “was attacked with fits of immoderate laughter, nor could the threats of his father or mother refrain him.”

Timothy Leary traveled to Mexico to experience psilocybin mushrooms himself. When he returned to Harvard in 1960, he and Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass) started the Harvard Psilocybin Project, promoting psychological and religious study of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs. Alpert and Leary sought out to conduct research with psilocybin on prisoners in the 1960s, testing its effects on recidivism. This experiment reviewed the subjects six months later, and found that the recidivism rate had decreased beyond their expectation, below 40%. This, and another experiment administering psilocybin to graduate divinity students, showed controversy. Shortly after Leary and Alpert were dismissed from their jobs by Harvard in 1963, they turned their attention toward promoting the psychedelic experience to the nascent hippie counterculture.

Back to Top

Uses

As of 2021, research conducted on psilocybin therapy included potential effects on anxiety and depression in people with cancer diagnoses, and alcohol use disorder.

As of 2021, research conducted on psilocybin therapy included potential effects on anxiety and depression in people with cancer diagnoses, and alcohol use disorder.

“It was a real surprise to see such enduring changes from just one dose of psilocybin,” said Yale’s Alex Kwan, associate professor of psychiatry and of neuroscience. “These new connections may be the structural changes the brain uses to store new experiences.”

Shrooms have the potential to aid in the treatment of depression, eating disorders and addiction, but the study of psychedelics and their applications in medicine and psychology is still in its infancy, hampered by its Schedule I Narcotics status and the United States’ War on Drugs. However, shrooms have shown promise in combination with psychotherapy. Psychedelic use, including psilocybin, can produce spiritual benefits similar to meditation or other mystical experiences though comparing subjective effects isn’t easily quantifiable.

A 2006 study by Roland R. Griffiths published in the journal Psychopharmacology found that users reported joy and extreme happiness, with elevations in how participants rated their “positive attitudes, mood, social effects, and behavior,” even two months after consuming psilocybin mushrooms. Volunteers reported increases in a variety of “mysticism” and “state of consciousness” categories, including “sacredness,” “intuitive knowledge,” “transcendence of time and space,” “deep felt positive mood” and “ineffability.”

67 percent of the 36 patients in the trial study described their experience with magic mushrooms as “either the single most meaningful experience of his or her life or among the top five most meaningful experiences of his or her life,” ranking it similarly to the birth of a first child. None of the participants rated their experience with psilocybin as “having decreased their sense of wellbeing or life satisfaction.”

In follow-up studies published in 2011 and 2017, Griffith found permanent positive effects of psilocybin use—including heightened openness, gratitude, forgiveness, coping and “death transcendence”—particularly when combined with other spiritual practices, like meditation. However, at least one of the listed effects failed to replicate in a subsequent study.

Research studies on the effects of these mushrooms have been conducted at the UK’s Imperial College London and the Beckley Foundation, as well as at Yale and Johns Hopkins University.

Back to Top

Formulas or Dosages

Dosage of mushrooms containing psilocybin depends on the psilocybin and psilocin content of the mushroom which can vary significantly between and within the same species, but is typically around 0.5–2.0% of the dried weight of the mushroom. Usual doses of the common species Psilocybe cubensis range around 1.0 to 2.5 g, while about 2.5 to 5.0 g dried mushroom material is considered a strong dose. Above 5 g is often considered a heavy dose with 5.0 grams of dried mushroom often being referred to as a “heroic dose”.

The concentration of active psilocybin mushroom compounds varies from species to species, but also from mushroom to mushroom within a given species, subspecies or variety. The same holds true for different parts of the same mushroom. In the species Psilocybe samuiensis, the dried cap of the mushroom contains the most psilocybin at about 0.23%–0.90%. The mycelium contains about 0.24%–0.32%.

A very detailed guide for anyone seriously considering use of magic mushrroms with dosing guide, cautionary instructions, etc. can be found on the Newsweek website.

Back to Top

Warning

The legality of the cultivation, possession, and sale of psilocybin mushrooms and of psilocybin and psilocin varies from country to country.

Back to Top

Resource Links

Futurity: ‘Magic Mushroom’ Drug May Repair Neural Links Depression Cuts

Yale University: Psychedelic spurs growth of neural connections lost in depression

Futurity: Stuff in ‘Magic Mushrooms’ Could Treat Major Depression

Johns Hopkins Launches Center for Psychedelic Research

Johns Hopkins University: Psychedelic Drug Psilocybin Tamps Down Brain’s Ego Center

Johns Hopkins University: Psychedelic Treatment with Psilocybin Shown to Relieve Major Depression

Johns Hopkins University: Researchers Urge Caution Around Psilocybin Use

Johns Hopkins University: Tapping into Psilocybin’s Potential

Wikipedia: Psilocybin mushroom

Johns Hopdins University: ‘Magic Mushrooms’ Help Longtime Smokers Quit

Johns Hopkins University: Single Dose of Hallucinogen May Create Lasting Personality Change

Newsweek: Magic Mushrooms Guide: Where Shrooms Are Legal and How To Take Psilocybin

The Guardian:

‘They broke my mental shackles’: could magic mushrooms be the answer to depression?

The Guardian: Magic mushrooms lift severe depression in clinical trial

The Guardian: Magic mushrooms ‘reboot’ brain in depressed people – study

Bibliography

![]() Psilocybin Mushrooms: Psychedelic Mushroom Types and Their Safe Use – Psilocybin Identification Book (Entheogens 2), by Hank Bryant

Psilocybin Mushrooms: Psychedelic Mushroom Types and Their Safe Use – Psilocybin Identification Book (Entheogens 2), by Hank Bryant

![]() The Psilocybin Mushroom Bible: The Definitive Guide to Growing and Using Magic Mushrooms, by Dr. K Mandrake PhD

The Psilocybin Mushroom Bible: The Definitive Guide to Growing and Using Magic Mushrooms, by Dr. K Mandrake PhD

![]() Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide: A Handbook for Psilocybin Enthusiasts, by O. T. Oss (Author), O. N. Oeric (Author), Terence McKenna (Introduction)

Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide: A Handbook for Psilocybin Enthusiasts, by O. T. Oss (Author), O. N. Oeric (Author), Terence McKenna (Introduction)